By Middy Tilghman, Simon Beardmore and Andrew McEwan

Note from the editor (SZ): In 2007 Middy Tilghman, Andrew McEwan and Simon Beardmore wrote the following grant proposal to fund an ambitious kayaking expedition to Tajikistan:

In the decade following its independence, Tajikistan was embroiled in a civil war that took a devastating toll on its population, and eliminated tourism. Only recently has the opportunity to explore the steep whitewater of the Pamirs, the world’s tallest mountain range outside of the Himalayas, become possible.

The same vast glacial systems and high mountains that produce Tajikistan’s whitewater also restrict access beyond its largest rivers. We will use these major rivers, marginally accessible themselves, as arteries of access to smaller, more remote rivers. Our experience with extended, self-supported expeditions will allow us to paddle two of these large rivers, the Muksu and Obikhingou, down to the mouths of un-run, low-volume tributaries with the supplies necessary to explore and descend these inflowing creeks and rivers. We will kayak and explore almost 300 river-miles, over a third of which has never been run.

Itinerary

8/2: Arrive in Dushanbe, Tajikistan.

8/2-8/21: Purchase provisions, and attempt several rivers and creeks of western Tajikistan’s Fann Mountains. Return to Dushanbe.

8/21-9/4: Obtain permits and attempt several first descents of the Surkhab River tributaries- the Ptovkul, Kafmarchona, and Garub Rivers.

9/5-9/9: Drive to Khorog and re-supply.

9/10-9/25: Paddle and Explore the Muksu Watershed:

- Paddle 143 miles (48 miles of first descents).

- Drive the Pamir Highway to the Takhtakorum Pass.

- Hike 15 km over a 4,500 meter pass to the glacier that supplies the Belandkyk River (headwaters of the Muksu).

- Descend the Belandkyk, and deposit cache at the confluence of the Belandkyk, Kayndi, and Sauksu rivers.

- Hike up and descend the Kayndi and Sauksu Rivers, both first descents.

- Continue down the Class V canyons of the lower Muksu.

9/25-10/1: Return to Khorog and re-supply.

10/2-10/18:

- Paddle and Explore the Obikhingou Watershed (145 river-miles, 55 miles of first descents).

- Drive up the Vanch River valley to Poimazor, hike over a 4,200 meter ridge to the Garmo River.

- Descend the Garmo to a confluence of two unnamed tributaries and Obimazar River, deposit cache, hike up, and attempt first descents of each.

- Continue down the Class V Garmo and Obikhingou Rivers.

10/18-10/22: Return to Dushanbe.

10/26: Depart Dushanbe.

Andrew McEwan, Simon Beardmore, and Middy Tilghman have taught, paddled, and traveled together extensively in North American, Europe, Oceania, and Central Asia. With over 25 combined years of endurance training and racing as members of the U.S. National Wildwater Team, we have successfully completed ocean and river expeditions throughout the world. Our team has the unique combination of fitness and skills necessary to accomplish our ambitious goals in Tajikistan.

Most recently, we descended the Sary Jaz River from Kyrgyzstan into China. Our experience in Central Asia will be critical for managing the logistics in Tajikistan, one of the region’s more rugged, infrequently visited countries. The endurance acquired from our experience racing and training has proven critical for long, demanding trips in severe settings like the team’s 2002 Barrenlands Wildwater Expedition, which successfully explored 1,200 river-miles in 50 days in the Canadian Arctic. This fitness and expedition experience combined with our extensive preparation and style of deliberate expedition paddling provides us with the skills necessary for remote, self-contained river exploration among the giant peaks of the Pamirs.

Together we have tested our limits in the grueling training and intensity of international competition, on remote New Zealand mountaintops, and in some of Central Asia’s most difficult whitewater. Our mutual trust and confidence under stress is our team’s most hard-won and valuable asset.

The Expedition Begins:

SZ: The team maintained journals and a blog, published here, throughout their travels.

August 17, 2007

The bureaucratic maneuvering is at last complete. We are duly registered with Tajik KGB and clear to go paddling, no thanks to our own abilities. Our work over our first few days here was worth exactly nothing. In the end we paid Ichboll at a tourism company to do it for us.

We met with a real-estate agent, Akbar, who helped us find a home while we drank his vodka and ate his food. We moved into a charming two room hovel a block and a half from the presidential palace. There are some minor issues- flooding, flies, forward chickens, but it is cheap and conveniently situated downtown.

Thursday we finally paddled on the Karatag River west of Dushanbe. Simon, convalescent of elbow, trekked deep into the mountains alone to scout a few rivers.

Below Hakime the Karatag enters a gorge and gets down to business. It was so continuous that modestly difficult drops were portaged for fear of being pushed into subsequent drops out of sorts. Class V- rapids were stacked one on top of another, and connected by honking wavy current. We carried the big stuff. Maybe if there were less water. Maybe if all the rocks were not placed so inconveniently. But as it was we ran a lot of super continuous Class IV and the occasional Class V. That night we camped beside a monstrous drop we unselfishly left for the second descenders

Soon after, we headed east for a few nearby creeks and then over the mountains to the north.

August 24, 2007

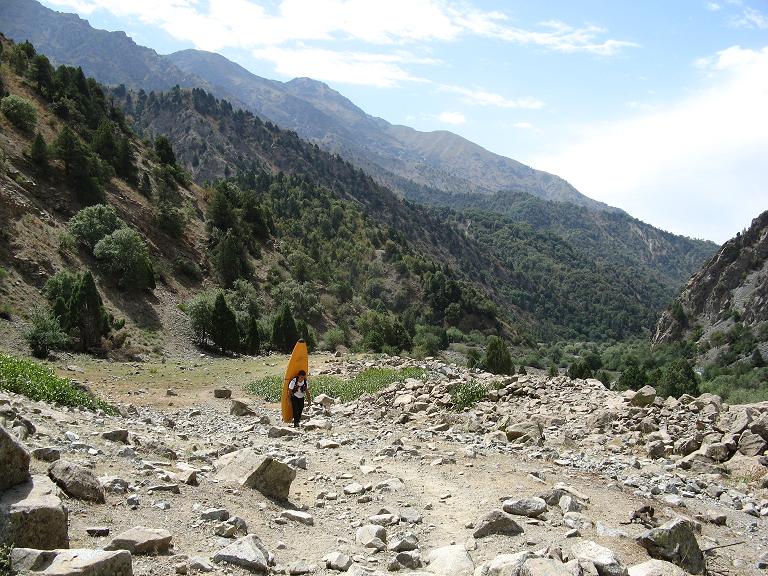

Having recovered Simon from his extended scouting mission, during which he shepherded 35 sheep 35 miles over four mountain passes, we stocked up on provisions and left Dushanbe for the mountains again. We caught a ride east to the town of Romit, then hitched a cheap ride in an old army convoy truck, passing by the creeks that Simon’s reconnaissance had deemed too inaccessible, too unrunnable, or worst of all, too easy. At 8,000 feet, we reached the end of the road, and the town of Refugar. When we arrived, the shadows had fallen, but we weren’t interested in sticking around, as a high pass stood between us and the put in. We loaded our boats, and shook hands with the skeptical Refugarans. We climbed a few hundred feet, lost the path, and retired early.

The next morning, we enjoyed an eight hour jaunt over a grassy saddle at 10,500 feet, then dropped down to the Yagnob river below. The scenery was lovely, and the Yagnob didn’t disappoint. We paddled to the first gorge and set up camp. The first two stretches of whitewater looked fun, but presented the very real, heartbreaking threat of drowning us. They each consisted of a hundred yards of intense, runnable whitewater followed by vicious pin spots, with no suitable egress between. But the next few miles were awesome–continuous, steep, and pushy. We ate lunch in a glen at the bottom of the canyon where a tributary crashed down the side of the gorge, opening it up enough for some trees and wildflowers to grow.

Just downstream of our lunch spot, the river sluiced between a giant rock wall and a stack of boulders. We ran an eight foot drop into a mini-gorge that led into an undercut wall. Andrew went last, and he slammed into the wall; luckily the current wasn’t pushing too hard, and he managed to eddy out. Downstream, the water folded under two huge boulders, but it was possible to paddle underneath, with room for kayaks, torsos, and heads.

The close call of the day occurred when Simon probed an undercut slot backwards. From the eddy downstream Middy saw a flash of paddle, followed seconds later by Simon, shooting out of the water in a giant, stress-relieving ender. The final rapid of the day was a big flushy drop with a pushy lead in. We scouted and debated for a while, but in the end, there was no reason to portage. We all dropped through the chaos without trouble.

Monday started with miles and miles of Class III, mostly an excellent chance to sunburn. But our little Yagnob was growing up; the waves and holes were meatier, and eventually the river turned serious. It went through a cool canyon with big whitewater; rocks balanced on packed dirt pedestals, and big walls in the distance. We were forced to carry the lead-in to a cool, angsty, adolescent drop, because of a shallow landing, but we seal-launched directly below it, and ran through a big, over hung S curve.

Another rapid flipped Andrew and Middy in an enormous hole. They both rolled just before the lip of a scary looking, but friendly second drop. The change in volume was affecting our ability to judge the river’s features. Nonetheless, we made it through the canyon and another shorter one below it before stopping for the night.

The next day’s story is sadly not one of whitewater but rather one of sweating under the sun and breathing dust. We returned to Dushanbe for further visa negotiations. We stashed the boats and planned to return to finish the Yagnob/Fandarya . We found a suitable spot where most of a mountain side had slid into the gorge, covering the river with massive boulders. Below, we found an overhang, hidden from the road above, where we left boats and gear.

Exhausted and sunburned, we walked up to the dirt and gravel track (read ‘national thoroughfare’). We had hoped to flag a ride to Dushanbe, but cars were almost as scarce as shade, so we hopped a crawling Kamaz truck to Anzob. From there, we eventually got a ride over the pass, and down the dusty road to the capital city.

The next phase of the visa solution started, requiring our passports until Monday. We couldn’t wait that long to get back to the rivers, however, so we left the next day. In other news, the expedition was happy to welcome a new addition to the fly hovel: a sheep on the concrete front lawn. Sadly, he was not long for this world.

September 2007

A lot has happened, much of which must be elided for reasons of conciseness. But dullness seems the least likely of all the unexpected things that happen to you in Tajikistan.

It began before we even got back to our boats. Our driver, Mansour, convinced us to take an alternate route around the pass via an unfinished tunnel. The State Department website specifically recommended avoiding the route, but Mansour seemed confident, so we agreed. He stopped a few times and talked to the guards stationed to protect people like us from ourselves. For a little money though, they were willing to turn a blind eye to our safety. The tunnel was terrifying. One hundred cfs of glacial mud and water ran down the road from the high point. It was hard to gauge its depth, however, as lighting consisted of an 80 watt light bulb every 150 feet. Fifteen long minutes after entering the tunnel, we emerged, then descended to the Fandarya and our boat stash.

The whitewater picked up right where we had left it—biggish Class IV. It disappeared underground, reappeared, and entered a wicked canyon where it plummeted into rocks and disappeared completely under boulders. Under the good-natured watch of Kamaz truck drivers, we lowered our boats down sharp and rumbling decline and paddled the rest of the canyon.

That night, Andrew spilled fuel while trying to fix our stove. It ignited, and fire consumed our fuel pump in spite of our feeble measures: we poured rice on it, beat it with a sleeping pad, and finally flung the whole jet of flame into the river. We eventually just watched it burn and ate our sausage and cheese with bread.

The next day, the river almost doubled in size with the additions of the Iskanderdarya and Pasrudarya. Middy, the odd man out, hiked up the Pasrudarya in search of whitewater but found it lacking.

Armed with the additional volume, the Fandarya entered a menacing, narrow gorge. For a while, it was big, easy water until it eventually reached a canyon with no escape. Andrew hiked up to the road and walked downstream to scout. It was a matter of sneaking right against the canyon wall, then ferrying left to boof a shallow pourover, hitting two left slots, and jetting back right through enormous boils to catch an eddy at the edge of an unappealing drop we wished to portage. Down in the canyon, the water was bigger than expected. The ‘shallow pourover’ was barely recognizable and the final ferry a battle across and out of a boily eddy to the right-hand side. But we all came through fine

Later, we paddled a huge, impressive, but easy rapid formed at the bottom of a scree field that rose hundreds of feet to the road. It was massively powerful, presumably because the river dropped fifteen feet, whipping water over smooth rocks. After a few more pretty canyons we camped near the end of the river and cooked our dodgy Tajik sausage and highly processed cheese on a lump of starch formerly known as rice.

In the morning, we paddled to where the beautiful green Fandarya submerged itself in 5000 cfs of brown, glacial Zeravshan. Middy and Andrew caught rides west, to scout possible runs, while Simon stayed in an orchard with the boats and battled some runs of his own.

Middy’s bid for most miserable night involved a 40 km hike, from four p. m. until two a.m., up the Kshtut River. Upon returning to the road, he was blown off by all three cars he saw and spent the night shivering in a T-shirt.

Andrew’s trip was also dismal, although certainly not due to privation. Near the Subashy River, he was given full guest treatment, consisting of abundant food, bed, and the heinous Tajik nos: some kind of chew that’s like simultaneously experiencing every time you’ve ever been car-sick. He threw everything up in his host’s courtyard.

Our scouting revealed two creeks we didn’t want to run, so we opted for the raging Zeravshan instead.

After serious bargaining, we left Aini for the town of Madrushkat four hours up the Zeravshan River valley. Farther upstream at the river’s glacial source, there are canyons with big rocks, but the need to return to Dushanbe in four days to claim our new visas meant Madrushkat was the end of our drive.

Carrying our boats down to the river, we descended into a scene with so many strange happenings grafted together it was like a Tajik political poster. In an average poster, the president is giving a speech or harvesting wheat in a multi-color wool sweater, a hill-side is being blown to bits in the name of a road’s progress, and military planes are in formation overhead, all under a clear sky and bordered by a handy calendar. We walked into a scene where children threw their apple harvest into the air and wailed in full prostration upon seeing us, a sandstorm blew down the valley, and rain fell from clouds high above the mountain peak The sun damped out by the sandstorm, we left this scene on 4000 cfs of muddy water with rocks rumbling and cracking on the river bed below our hulls. Convinced by our ever present sunburn to leave our tarp in Ajni, we passed our first nights of Tajik rain in a farmer’s day hut at the base of a tributary and scouted the creek with this friendly farmer the following morning. After this fun but fruitless scout, we returned to the Zeravshan and bounced our way through small gorges and small whitewater.

The whitewater grew with the river’s gradient and the depths of its canyons. On day two, we snuck booming drops and ran sheer rock canyons with no defined whitewater only surging, boiling messes.

We had nearly lost our enthusiasm for walking up the low volume, donkey-punch gauntlets that were the Zeravshan’s tributaries, when our efforts paid off. A small creek cut through the canyon wall of the main river. This mini-gorge was 300 feet long, four feet wide, and 50 feet high. The little creek pushed 60 cfs down small drops and off a ten foot drop into a smooth cauldron. The cauldron’s exit to the blue sky above was a narrow window as was its exit to the main river which required us to duck the overhanging rock wall as the creek carved its final turn. It was beautiful, runnable, and a fun change from the Zeravshanness.

The third day was filled with big whitewater that kept us happy and alert. The highlights were two drops we had seen on our drive up. One was a river-wide hole runnable with a face full of water on the river right. The other was 300 yards of waves big enough to hide Simon and his boat when they flew by Middy, waiting in the bottom eddy, unseen. By midday on day three, we were back in the orchard in Ajni and began the voyage to the Varzob River and Dushanbe.

We left our sacred grove, and headed into Ajni to negotiate a ride to Zide, a small town at the headwaters of the Varzob River. As we strode three abreast across the dusty bridge into town, an eerie quiet surrounded us. It would have been fitting if a tumbleweed had rolled by just then, and a gang of banditos waited on the other side of the bridge for a high noon shoot out. Actually, the banditos turned out to be Chinese construction workers, and rather than an anticipated blood bath, road closure for paving had deserted the town. Six hours later, when the road re-opened, we headed out, determined to spend the next day on the water.

After 10 miles, we reached the tail end of 300 cars and trucks waiting for a second closure, caused by landslide from the recent rain, to open. The ensuing traffic chaos set us back another couple hours, but we pressed on. The final delay, which cost another hour, involved the resurrection of our clinically dead Lada after half a dozen jump start attempts. Eventually though, bleary-eyed, we collapsed into sleeping bags at four a.m., the sound of the Varzob murmuring in the background.

Hours later, as we approached looming horizon lines, the murmuring had become a definite roar. Within a few miles of starting, tributaries had swollen the river from 200 to 500 cfs, and the river started dropping. Consisting of tight lines through boulder strewn rapids, the Varzob was a far cry from the sheer volume of the Zeravshan. Despite frequent scouting, progress was steady, requiring only one portage around a river-wide sieve. After lunch, we reached a picture-perfect section of river, with five clean drops and slides along a straight-away. We battled pushy currents, and perhaps fatigue, as we made our way downstream toward Dushanbe. Our plan was to paddle as far as time permitted, then catch a ride the rest of the distance to the city. We reached a sensible stopping point late in the afternoon, when after a few sloppy lines, Simon dropped into a sticky hole. After 90 seconds of side-surfing, he finally extracted himself, and paddled to an eddy downstream.

Worn out, we walked up to the road, and fortuitously caught a ride in an empty gravel truck after a few minutes.

We stopped to fill the truck with sand at the driver’s house. He was keen to show us his 1970’s flatwater kayak, stored diligently on the roof of his shed. Dushanbe used to be a Soviet training center for Olympic canoe and kayak. We had secured visas for another month, and in a couple days time, we’ll head east to the creeks near Novabad, Tajikabad, and Djirgital.

Andrew, Simon, and Middy

All photos courtesy of the team. SZ.

Leave a Reply